Gender Equality: More Than an Option

Gender equality is one of the United Nations' (UN) 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With these SDGs, we try to make the world a better place. If we do not pay attention to women, this will be a difficult job. The UN member states aim to achieve these goals by 2030. The Netherlands Enterprise Agency also wants to contribute to them.

The position of women is of global importance. Not only for achieving SDG 5: Gender equality and empowerment for women and girls. But also for SDG 8: Sustainable economic growth. That is why every project that the Netherlands Enterprise Agency carries out must meet gender objectives. We can aim for specific gender objectives in many ways. But how do we do this effectively? And what is the impact?

This article tells the story of Sana (34 years old from Mombasa, Kenya), who received support through the SDG Partnership Facility (SDGP). This is one of the many programmes the Netherlands Enterprise Agency carries out. Her story shows the challenges that women face. This story also shows how the programmes try to promote gender equality. Amarens Felperlaan is a senior project advisor at the Netherlands Enterprise Agency. She explains how we fight gender inequality. She also gives some practical tips and advice. But first, an answer to the question: What is gender?

What is gender?

We use the word gender for the socially created differences between women and men. Your sex is biologically determined: most people are born with female or male biological characteristics. Society teaches girls and boys to become women and men, respectively. This acquired behaviour creates a specific identity and role: gender.

People often find themselves in different positions in society based on their gender. When there is gender equality, there is no discrimination based on biological sex or people's roles in society. This means that people of different genders can access the same opportunities, resources and services.

What does the life of a woman in Mombasa look like?

In the late 1990s, in Mombasa, Kenya, Sana, 11 years old, wakes up in the middle of the night with a vision of her future. "When everybody in the house was sleeping, I would cry and pray. God, please, I do not want this. Please." Sana is not beaten or mistreated. But her chances of self-development are slim as the third girl in a family of 9. Her father works hard to provide food and shelter for the family, and Sana's 2 brothers are valued highly. Her oldest sister has already been married off and lives with her husband in Yemen. Sana does not want this to happen to her. Yet, she is not exactly sure how to prevent it.

In Mombasa, Sana's childhood experience is no exception. There are many conservative families in the city. Her father gets angry if she does not come home on time. If her younger brother is late, one of the girls has to set the table for him again later in the evening. "They were always treated as worth more than us girls. I served my brothers, but inside, I exploded." She held back because she wanted to use her energy for something else. Because Sana wanted to accomplish something. But it did not work out immediately. She stayed at home for years, waiting for a husband. "Ever since I was a child, I did not like the lifestyle I saw around me. I prayed for a different life. If nothing changed, my life would become like that of my eldest sister, aunts and other married women. Always busy working in the house. They did not like it, but they had no choice. I was hoping that I would have a choice."

And after a long time, she did. Sana came across BOOST in Mombasa, an SDGP project that the Netherlands Enterprise Agency supports. But first, before getting where she wanted to go, she had to fight a personal battle.

Are women 'competent to act'?

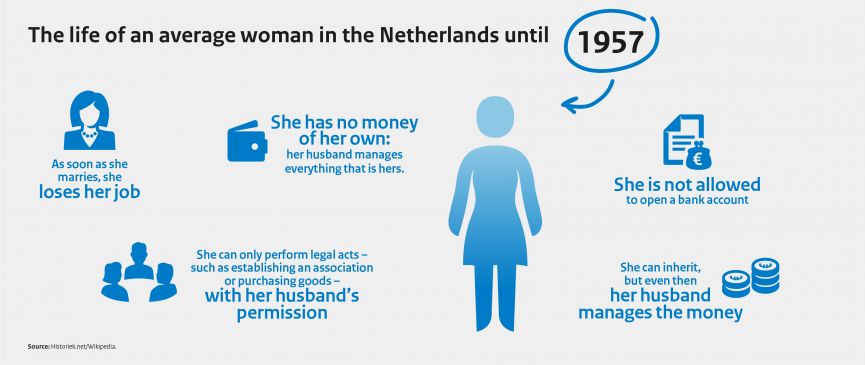

Sana's early life is the reality for many girls and women worldwide. But, not so long ago, it was the same for women in developed countries. 2 or 3 generations ago, they experienced similar conditions. After getting married, they would lose their jobs as they were regarded as incompetent to act. This did not change until 1 January 1957. On that date, a change in the law came into force in the Netherlands that meant women were legally 'competent to act'. From that point on, women could, for example, establish an association or enter into a contract by themselves.

The life of an average woman in the Netherlands until 1957:

- As soon as she marries, she loses her job;

- She has no money of her own: her husband manages everything that is hers;

- She can only perform legal acts, such as establishing an association or purchasing goods with her husband's permission;

- She can inherit, but even then, her husband manages the money;

- She is not allowed to open a bank account.

Source: Historiek.net/wikipedia

Politician Corry Tendeloo became a member of the Dutch Parliament because she wanted to fight for gender equality. In 1955, she submitted a political proposal against the ban on married women working. This proposal only became law by a small margin: 46 members of parliament voted in favour, 44 against. All 8 women members of parliament voted in favour. One of them was Marga Klompé, who later became the first woman minister of the Netherlands. The Tendeloo motion changed the law and, as a result, women's lives in the Netherlands. From 1 January 1957, they were legally competent to act. The surrounding countries also changed their laws around the same time.

Yet, there are still countries where a woman is considered incompetent to act after getting married. In Egypt, for example, a married woman may only leave the house with her husband's consent. Otherwise, she loses the right to financial support. In Israel, a woman needs her husband's permission to file for divorce. And in many countries, such as Burkina Faso, forced marriages are still common. In many countries, women cannot have land rights and thus cannot build a life independently. It is impossible to improve the position of women in those countries. Remember, it was the same in the Netherlands not that long ago.

Where can you see inequality between men and women?

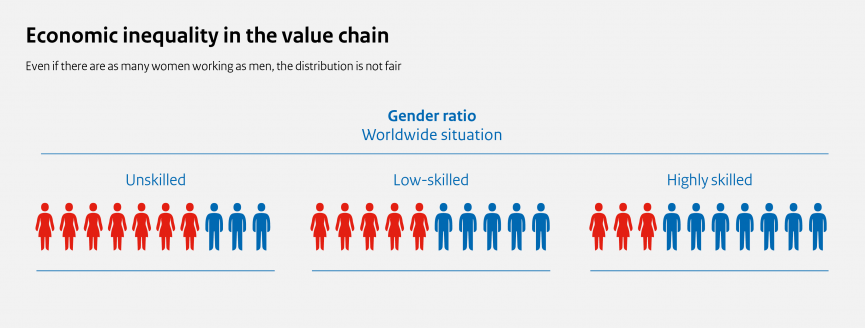

We see differences worldwide. Women are more likely to work in low-wage sectors, doing unskilled work with fewer job securities than men. They are also under-represented in decision-making positions in the science and technology sectors.

One explanation is that women still do not have the same education and training opportunities as men. Another is that women are paid less than men for doing the same job. This is true all over the world. The global wage gap between women and men is around 23% (source: UN). So, for every euro a man earns, a woman only earns 77 cents. This difference is the result of many factors combined. These include but are not limited to women being overrepresented in underpaying sectors, lack of education and unpaid childcare. These circumstances will not disappear overnight. The wage gap is a symptom of much bigger underlying problems.

There are also differences in caretaking tasks. Women usually do more unpaid work such as cooking, cleaning, fetching firewood or water, and caring for children or other family members. This reduces their chances in the labour market. They are sometimes forced into part-time work because they are so busy at home.

Another problem is that women find getting loans from a bank or financing institute harder. When they get a loan, it often has a higher interest rate and stricter requirements. This makes it more difficult for women to pay for an education or start a business.

Finally, there are conscious and unconscious prejudices against women. Women are less likely to be perceived as leaders. If they do show leadership qualities, these are evaluated less positively. This is one of the explanations for the fact that few women work at higher levels in organisations. We see that women mainly do unskilled or low-skilled work globally. Men do most of the higher-skilled work.

Economic inequality in the value chain. Even if there are as many women working as men, the distribution is not fair.

Worldwide gender ratio situation (rounded percentages):

- Unskilled: 70% women and 30% men;

- Low skilled: 50% women and 50% men;

- Highly skilled: 30% women and 70% men.

How big is the gender gap?

The Global Gender Gap Index from the World Economic Forum (WEF) examines the gender gap: the social and economic inequality between men and women. This research looks at 4 categories:

- Economic Participation and Opportunities;

- Educational Level;

- Health and Survival; and

- Political Power.

Every year, the WEF publishes an extensive report on the worldwide gender gap. The report contains averages and upward and downward peaks.

What is noticeable is that the educational inequality between men and women is, on average, decreasing. Girls and young women perform well at school and even stay in education longer than boys. But, in some countries, the gender gap in education is still significant. This is the case, for example, in Afghanistan (with a gap of 51.4%), Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Yemen.

Unfortunately, income inequality is a problem everywhere. Even in developed countries, women earn on average 15% less than men for doing similar work.

The gap in joining the labour market is as high as 82% in countries such as Afghanistan, India, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria and Yemen. The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 states, "One of the main causes of gender inequality is the under-representation of women in the labour market." Participating in the labour market is essential for women to become economically strong. It is also a way to work towards diverse, inclusive and innovative organisations. Worldwide, almost 80% of men aged 15-64 take part in the labour market. In the same age group, only 53% of women do. Addressing barriers for women remains a priority for policymakers and businesses in all countries.

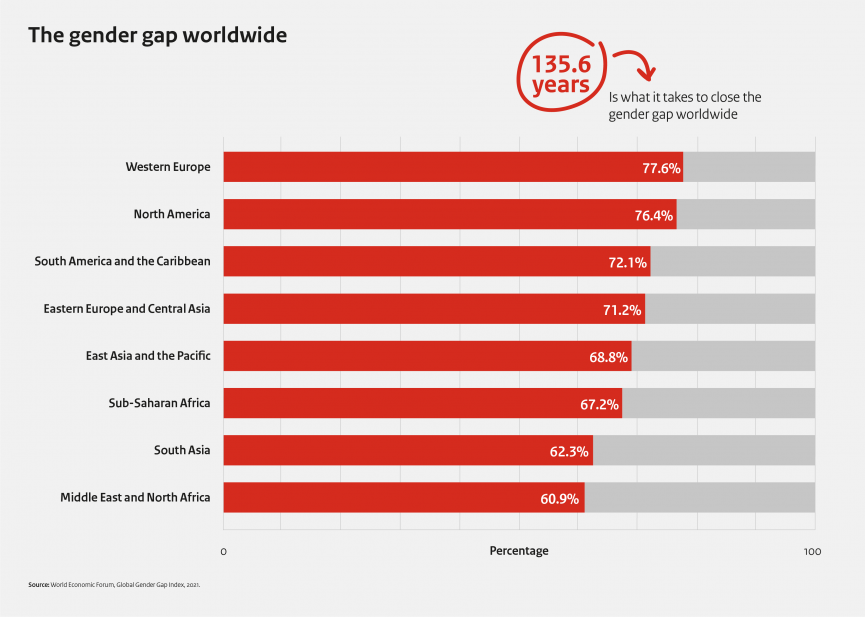

Globally, the gender gap has now closed by 68%. It will take almost 136 years to close it entirely at this rate. To speed up this process, the Netherlands Enterprise Agency focuses on several projects and programmes on SDG 5: Gender equality and SDG 8: Fair work and economic growth.

Globally, the gender gap has been closed by the following percentages:

- Western Europe 77.6%;

- North America 76.4%;

- South America and the Caribbean 72.1%;

- Eastern Europe and Central Asia 71.2%;

- East Asia and the Pacific 68.8%;

- Sub-Saharan Africa 67.2%;

- South Asia 62.3%;

- The Middle East and North America 60.9%.

Right now, it will take 135.6 years to close the global gender gap.

Bron: World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Index, 2021.

What impact has the COVID-19 crisis had on the gender gap?

Over the past 2 years, the gender gap has not narrowed as much as the WEF expected. This is partly because WEF added new countries to its report. But it is also due to the coronavirus pandemic; this crisis has increased the inequality between men and women worldwide. The pandemic has affected women more than men. According to the International Labour Organization, relatively more women are losing their jobs: 5%, compared to 3.9% of men. This is because women are more likely to work in sectors affected the most by the coronavirus crisis. In many countries, childcare facilities, schools and care institutes for the elderly have closed several times. As a result, there was more pressure on caretaking tasks. Men often expect women to fulfil these tasks, so they have less time for paid work. This illustrates the unequal division of labour between women and men.

Why does the Netherlands Enterprise Agency pay attention to gender in its programmes?

Gender is a topic that receives attention in all Netherlands Enterprise Agency programmes. We do that on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Amarens Felperlaan is a senior project advisor for public-private partnerships at the Netherlands Enterprise Agency. She is involved in several projects. Projects often focus on improving food security or stimulating the private sector in low and middle-income countries, especially in Africa. Amarens explains, "My first project focusing on gender was a coffee project in Uganda and Kenya. In this project, we worked with an NGO that had great ambitions. It had a gender-transformative approach, and the NGO tracked whether the project achieved its goals. At the Netherlands Enterprise Agency, we find these topics very important. We learn from the knowledge and experience of NGOs. We use this to integrate gender into all our projects better. The Netherlands Enterprise Agency wants to see gender objectives reflected in every project or programme, and we assess proposals on this basis."

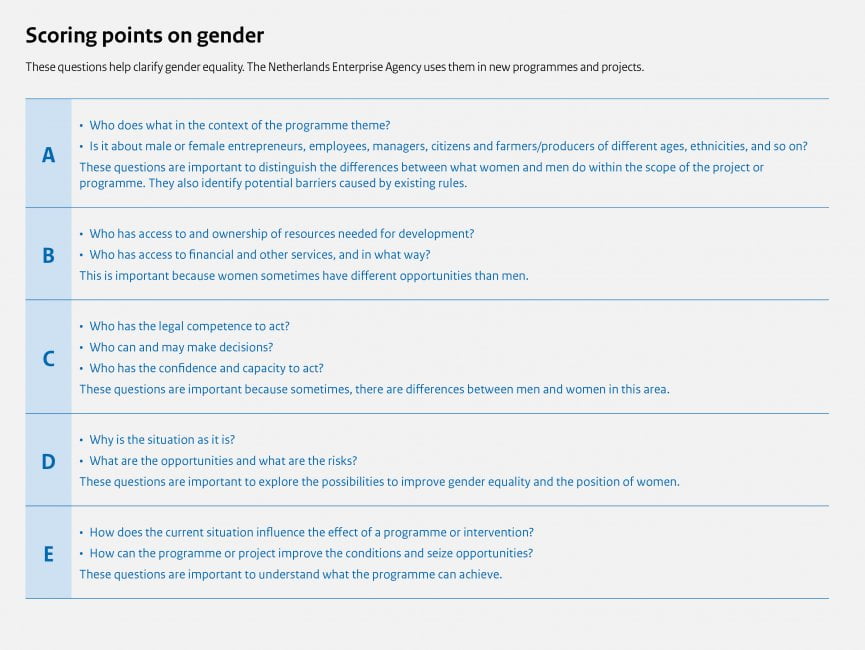

These questions help clarify gender equality. The Netherlands Enterprise Agency uses them in new programmes and projects.

- Who does what in the context of the programme theme?

- Is it about women or men entrepreneurs, employees, managers, citizens and farmers/producers of different ages, ethnicities, and so on?

These questions are important to distinguish the differences between what women and men do within the scope of the project or programme. They also identify potential barriers caused by existing rules. - Who has access to and ownership of resources needed for development?

- Who has access to financial and other services, and in what way?

This is important because women sometimes have different opportunities than men. - Who has the legal competence to act?

- Who can and may make decisions?

- Who has the confidence and capacity to act?

These questions are important because sometimes there are differences between men and women in this area. - Why is the situation as it is?

- What are the opportunities and what are the risks?

These questions are important to explore the possibilities to improve gender equality and the position of women. - How does the current situation influence the effect of a programme or intervention?

- How can the programme or project improve the conditions and seize opportunities?

These questions are important to understand what the programme can achieve.

Our programmes aim for economic equality, which does not necessarily have to be the programme's primary goal. For example, a project can focus on trade, food security or water. Allowing women to join is one way to achieve the goals.

So, before a project starts, we pay attention to gender. We want this to be a focal point throughout the project. A project that also works on economic equality will achieve better results. Previous project results show that the economic involvement of women leads to a greater connection with and influence on society. We refer to this involvement as economic empowerment. We speak of economic empowerment when women have more opportunities, and have more say in important decisions. In their homes, their communities and their lives.

How to achieve gender equality at home

The coffee project in Uganda and Kenya aimed to improve the economy. Equality between men and women was part of it. Amarens visited the project in Uganda. "What I found impressive was that they had a 'gender champion'. This person working for gender equality was a man. At first, that surprised me. But later on, I understood that he could inspire other men. He told those who were perhaps afraid or insecure: "I am still okay. I am a proud man." He was happy with the change in his household. He told other men how interesting it is to talk to your wife and make a plan for the future together."

So, are men afraid? "At first, yes. When women start earning more, men lose some of their power. This can create tension at home. For example, about what they spend money on. The relationship changes." Amarens shows that it is not enough to give women work. We must also pay attention to the relationship with their husbands and the changes at home. "In the end, it also has advantages for the man. He is no longer solely responsible for the income."

At the start of a programme or project, the Netherlands Enterprise Agency analyses these aspects. The outcome of the analysis helps choose the right objectives. For example, a project should provide a woman with work and look at aspects that may be hindering her (economic) position. It really helps a woman if she gets room to make decisions and manage her own money.

"It is not enough to give women jobs. There also needs to be more awareness at the household level."

Is it not enough to give women jobs?

Amarens has also seen projects in which there was less attention on gender. For example, women were given jobs in a factory where most workers were already women. "This may tick a box because more women get jobs, but you have not changed any role patterns." What we want to achieve goes beyond that. It is about real changes in the lives of women. It is about a casual effect: because she gets more of a say, her sisters, nieces, daughters, friends, and their sisters, nieces, daughters and friends get inspired too.

Gender champions

Back to Mombasa, where something has changed in Sana's life. Her sister, the second in the family, and her uncle caused the change. "My father was always very rigorous. He worked a lot because he wanted to give us a better life. But when he was at home, he would shout at us. It felt like he was hurting us on purpose, even though he was not." Her second sister was brilliant and did well in school. "My uncle told my father it would be good if she continued school. My father agreed and let her continue her education. While my sister was opening doors, I was walking behind her praying!"

Today, Sana slowly, very slowly sees an opening, also for her. Like her sister, she eventually studied computer science at the Islamic University in Uganda (IUIU). "I was so excited! It felt like I had finally found freedom. My father was not there; I could walk around the campus freely without asking permission for everything." Her father believed that his children were smart and could achieve a lot. Sana's uncle, sister and father became gender champions: people who work for gender equality. At least in education.

How can we ensure equal opportunities for women?

Suppose many women are already working in a peanut factory for low wages. Would it help to have more women working for those low wages? Does it change anything? Unfortunately, not really. We do not see a transformation until women have the same chance to do the same work as men.

Sometimes, transformation goes in the opposite direction. According to Sullerot's Law, named after Evelyn Sullerot, something strange happens when many women enter a specific profession like teaching. The profession becomes less prestigious. What was once a man's job is now a woman's but with lower wages.

In projects the Netherlands Enterprise Agency carries out, the focus is primarily on equal opportunities. The BOOST project is an example of this. This project is a collaboration between Close the Gap Kenya, the Kenyan governmental organisation National Industrial Training Authority (NITA), and the Dutch parties MDF, Crosswise Works and Goodup. The project wants to create more employment in Mombasa, stimulate the circular economy and give more people access to sustainable technology. Young people and women are a focus group in the project because this contributes to the other objectives.

"BOOST aims for local impact and added value. Their desire to make a difference matches their target group of young people and women."

When Amarens read the plan for Kenya BOOST, she was immediately enthusiastic. "It deals with many of the issues that we consider important. For example, the circular economy, empowerment of youth and women, and a lasting impact on gender equality. In Mombasa, women are a vulnerable group. It is not easy to reach them and get them on board. In Nairobi, Kenya's capital, many young people come from universities eager to get started. Mombasa is different. Especially if you want to help young people and women." To reach the target groups, BOOST works with women's hubs or local networks of women. The project works with a gender expert, Eva Kimani, a successful Kenyan woman. She wrote a plan and started to develop it. Eva explains, "We want to teach young people and women and provide them with opportunities so they can advance in their careers or as entrepreneurs."

What are the benefits of gender equality?

The worldwide economy gets a boost and society benefits from gender equality. Investing in women is a win-win for many reasons.

- Companies with at least 15% women in senior management are 50% more profitable.

- When women earn money, it has a direct positive impact on their health, education and the well-being of their families and communities. Every paycheck for a woman is an investment in the human capital of the next generation.

- More gender equality means more income equality. It encourages diversity in the economy, making it more resilient.

Life-changing moments

Meanwhile, the sun begins to shine for young Sana in Mombasa. She is having the time of her life at university. Her sister finished her studies a year before she did. To Sana's surprise, her sister did not go to work but served her family instead. "She just stayed at home and prepared meals for the family. It was exactly the same subordinate role as before. I did not understand it. Why would she go back to such a life after university? When I asked, she said she was not allowed to think or contribute to anything." Their father had become afraid. Afraid that those around him would condemn him for his choices. But, he was actually condemned for wasting talent. Sana's uncle spoke up and arranged work for Sana's sister. All their efforts had almost been for nothing. But their father eventually agreed.

A year later, Sana also graduated from university. She started working in telecommunications and fibre optics and further distanced herself from her father. "It took him a long time, but he eventually embraced the fact that his daughters are working women. My relationship with my father changed. He let me keep the money I earned to build my own life. When I became head of my department, I had to go to Nairobi for training and certification. The company wanted to pay for it. That was a life-changing moment. I was worth something, all on my own." Not everyone is as persistent as Sana or has an uncle who fights so strongly for her rights. That is why we need programmes that help women and encourage men to become gender champions.

Gender-transformative

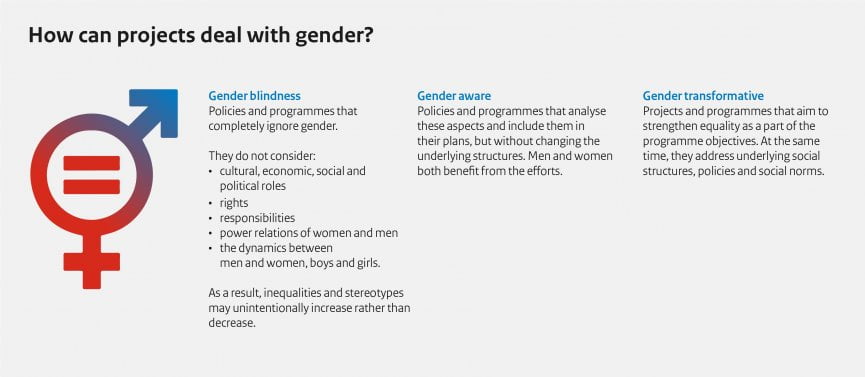

Amarens answers, "In such a case, we call it 'gender blind'. We do not accept these types of programmes. The problem with gender-blind programmes is that it does not consider the different situations or needs of men and women. A gender-blind project does not succeed in helping women; the problems remain or get worse. Being gender-aware, like in the factory example, where women already worked, and more women will work, is an improvement. It ensures that women can also benefit from the project. But our ultimate goal is to work in a gender-blind way. That is when perceptions really change.

In what ways can projects deal with gender?

Gender blindness: Policies and programmes that completely ignore gender.

They do not consider:

- cultural, economic, social and political roles;

- rights, responsibilities and power relations of women and men;

- the dynamics between men and women, boys and girls.

As a result, inequalities and stereotypes may unintentionally increase rather than decrease.

Gender aware: Policies and programmes that analyse these aspects and include them in their plans, but without changing the underlying structures. Men and women both benefit from the efforts.

Gender transformative: Projects and programmes that aim to strengthen equality as part of the programme objectives. At the same time, they address underlying social structures, policies and social norms.

What is a gender-transformative project?

Amarens explains, "Gender transformative projects are about empowering women. They can manage their own money and take on jobs that do not necessarily conform to cultural patterns. Each project has its own transformative goals." These are certainly not the easiest of goals.

Amarens recalls the coffee project in Uganda and Kenya, in which women became owners of a piece of land or trees to grow coffee. She continues, "There was a change in male-female relationships because they became equals. It is unusual for women to get access to a piece of land or trees because it is not common for women to own property." Access to land or even land rights for women is one of the project's objectives. The project's goals were even bigger: for women to hold managerial positions in cooperatives. "That turned out to be complicated," Amarens says. "You can only become a cooperative member if you are a landowner. And you can only run for the board if you are a member. We tried to discuss the rules that state that you have to own land. That is a long and bureaucratic process involving mainly men, who also must agree. You need many gender champions to make a change."

Amarens feels positive about the fact that the discussion has been started. "You want everything to work out, of course. You just have to think of what is possible in a certain region. In Northern Nigeria, for example, you have already achieved something if women take part in a training course. In Kenya, the position of women is generally better, so you can expect more. And even then, it is easier in Nairobi than in Mombasa. So we must be aware of the context and ensure the project fits in with the local culture. Also, the goal is ambitious enough but achievable," Amarens concludes. And that is precisely the case with BOOST. This project did not pick the easiest location, Mombasa, but it found a way to reach women and underprivileged youth.

"What people expect from men and women is still the same. I am 39 and even my educated mother occasionally asks: when are yu going to settle down? Sana gets the same questions. It is OK to work. Yet, people expect women to marry, have children and have husbands as breadwinners. The strangest thing is that even I recognise that feeling."

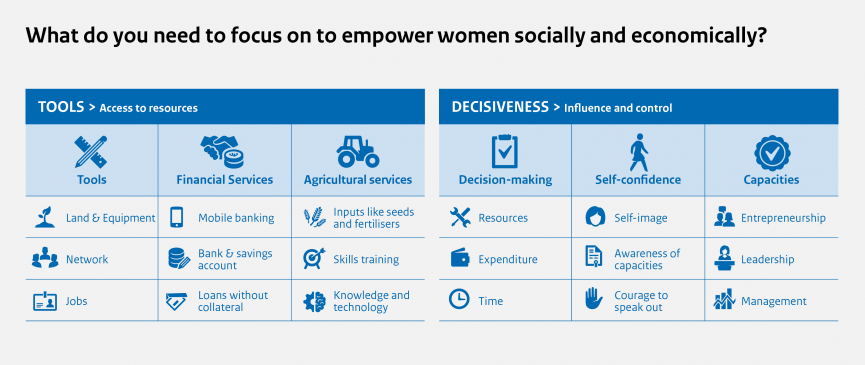

What do you need to focus on to empower women socially and economically?

Tools > Access to resources

Resources

- Land & Equipment

- Network

- Jobs

Financial Services

- Mobile banking

- Bank & savings account

- Loans without collateral

Agricultural services

- Inputs like seeds and fertilisers

- Skills training

- Knowledge and technology

Decisiveness > Influence & control

Decision-making

- Resources

- Expenditure

- Time

Self-confidence

- Self-image

- Awareness of capacities

- Courage to speak out

Capacities

- Entrepreneurship

- Leadership

- Management

What do women need for economic empowerment?

Women entrepreneurship is one of the focal points for economic equality. BOOST is also working on that. Project Manager Eva explains that one of the project's components helps women build their own businesses. "For example, they can make bags or jewellery from recycled materials. Through BOOST, they receive support and advice to make this a success."

Sana from Mombasa believed in herself and has managed to build a career against all odds. Last year, she joined BOOST because she wanted to grow even more. Now, she is still there to help other women. "I found my way because I knew which dreams I wanted to pursue. Now I want to help others make theirs come true."

According to Amarens, people like Sana are role models for other women in Mombasa. "If women show that they are successful, perhaps others will also dare stand up for themselves. Women like Sana are an inspiration to others." Project Manager Eva Kimani shares this view. "The women's project is a safe place where women can talk openly. Sana is now also an ambassador and a source of inspiration. She shows that it is possible to chase your dreams. The fact that Sana is doing something that men usually do, working in IT, makes her an ambassador."

How long is the road to gender equality in 2030?

Experiences like the gender champion in Uganda show that men also gain much from gender equality. Men will no longer be alone in making decisions. Men can talk to their wives about their future together. Men can be role models, showing other men that they can also benefit from gender equality. Equality does not mean that men and women have to do exactly the same jobs. What matters is simply that no one is disadvantaged because of their gender. Having fighters like Sana and projects like BOOST is fantastic. But ultimately, there is no equality until girls have the same opportunities as boys. Sana's story shows that she can achieve as much as her brothers. And yet, she almost missed out on the opportunity.

To ensure that girls and women get the same opportunities as men, we need a fundamental change, a transformation. We want to bring about this transformation by 2030. There is much work to be done before then. The enormous workforce worldwide is yet not being used to its full potential. But if we all make an effort, and all women and men become gender champions, it is within our reach. And there is no doubt that a gender-equal world would benefit us all.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs